For my first warp on the Glimakra, I decided to follow the steps on the set-up video. It used a back to front one cross method, which is what I've been using on my Schacht. However, it did a few things differently and I wanted to try these. For my first project, I wanted to weave a blanket for the WNCF/H Guild's service project, Project Linus. Until now, I hadn't had a loom able to weave the minimum 35 inch blanket width.

Of course on the set-up video, the loom is being warped for the first time, so the shafts are placed up on top of the countermarche, getting them out of the way for warping. Since my loom had already been woven on, the shafts were still tied to the lamms. After a little internal debate, I untied the lamms and put the shafts on top of the countermarche. I wasn't sure if this needed to be done for every new warp, but it let me follow along with the video more easily.

As you can see in the above photo, two long support sticks are placed on either side of the loom, resting on the front and back beams. The lease sticks and raddle rest nicely on these, making it easy to work with the warp and wind it on.

The raddle Dan made me for my Schacht isn't wide enough for this loom, but happily, I discovered that the top piece of my triangle loom worked very well, having enough length plus 1/2 inch spaces between the nails. After securing the warp with the lease sticks, I spread it out in the raddle.

The one cross b2f method I had been using was from Deb Chandler's Learning to Weave. It uses a threading cross only. In the Glimakra video, the cross is a raddle cross. No threading cross is used. The heddles are later threaded directly from the lease sticks.

The one cross b2f method I had been using was from Deb Chandler's Learning to Weave. It uses a threading cross only. In the Glimakra video, the cross is a raddle cross. No threading cross is used. The heddles are later threaded directly from the lease sticks.

In Chandler's method, an extra (lease) stick is placed in the the back loop of the warp (the end without the threading cross). This stick is then tied to the back apron rod. In the Glimakra video, the warp is actually transferred to the apron rod. On the left you can see that an extra (warp) stick has been placed in the cross with the lease sticks. This stick enables transfer of the warp to the apron rod.

The first step was to lay out the back apron cord and the warp, making sure both were centered. The warp was positioned so that it was divided into equal parts, each part to be placed between the corresponding apron cords.

The raddle Dan made me for my Schacht isn't wide enough for this loom, but happily, I discovered that the top piece of my triangle loom worked very well, having enough length plus 1/2 inch spaces between the nails. After securing the warp with the lease sticks, I spread it out in the raddle.

The one cross b2f method I had been using was from Deb Chandler's Learning to Weave. It uses a threading cross only. In the Glimakra video, the cross is a raddle cross. No threading cross is used. The heddles are later threaded directly from the lease sticks.

The one cross b2f method I had been using was from Deb Chandler's Learning to Weave. It uses a threading cross only. In the Glimakra video, the cross is a raddle cross. No threading cross is used. The heddles are later threaded directly from the lease sticks.In Chandler's method, an extra (lease) stick is placed in the the back loop of the warp (the end without the threading cross). This stick is then tied to the back apron rod. In the Glimakra video, the warp is actually transferred to the apron rod. On the left you can see that an extra (warp) stick has been placed in the cross with the lease sticks. This stick enables transfer of the warp to the apron rod.

The first step was to lay out the back apron cord and the warp, making sure both were centered. The warp was positioned so that it was divided into equal parts, each part to be placed between the corresponding apron cords.

One thing that was different with the way my loom is set up, is that the apron cords are not continuous lengths of cord looped over the apron sticks. The previous owner had cut the apron cords into equal lengths, and tied these onto the apron sticks from the warp and cloth beam. You can get an idea of this in the above photo.

Had these been looped over the apron stick as one long cord, I would have been able to transfer the loops of the cord onto my arm. However, since I was dealing with individual lengths of cord, I had to remove them from the stick in order to transfer the warp.

Had these been looped over the apron stick as one long cord, I would have been able to transfer the loops of the cord onto my arm. However, since I was dealing with individual lengths of cord, I had to remove them from the stick in order to transfer the warp.

I took my own photos, so you can't see that this is really a 2-hand task. I found that after deciding where the groups of warp needed to be placed on the apron rod, it was easiest to tie them onto bundles. Starting in the middle, I removed the apron cords from the apron rod until I got to the place for warp bundle I wanted to transfer. After I put the bundle onto the apron rod, I pulled the temporary stick out, replaced the apron cord and then moved on to the next bundle. I did this in two halves, working from center outward, since my warp is so wide.

After all the bundles of warp were transferred from the temporary stick to the apron rod and the cords replaced, I spread the warp out between the apron cords. The lease sticks remain in the warp to hold the cross.

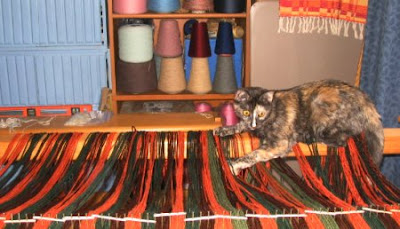

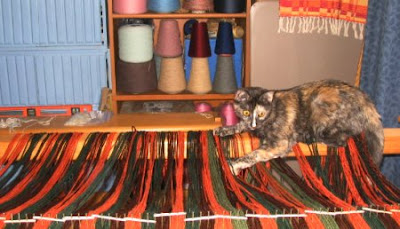

Since my warp is so wide, and I don't have enough 1/2 gallon milk jugs / weights, I tensioned the warp myself as I wound it on. I did have help . . .

Since my warp is so wide, and I don't have enough 1/2 gallon milk jugs / weights, I tensioned the warp myself as I wound it on. I did have help . . .

. . . but as you can see, it wasn't the useful kind.

I found that by using Peggy Osterkamp's "firewood method" (picture here), I could put my full body weight into it. Hopefully I have it tensioned evenly!

The loom also came with warp separator sticks. The previous owner's husband made this very handy storage container for them . . .

I found that by using Peggy Osterkamp's "firewood method" (picture here), I could put my full body weight into it. Hopefully I have it tensioned evenly!

The loom also came with warp separator sticks. The previous owner's husband made this very handy storage container for them . . .

The sticks are flexible enough to remove easily from the container through the long oblong opening.

After I finished winding on, the breast beam and knee beam were removed. The bench fits nicely inside the loom and I'm ready to take the shafts down from on top of the countermarche and start threading the heddles.

After I finished winding on, the breast beam and knee beam were removed. The bench fits nicely inside the loom and I'm ready to take the shafts down from on top of the countermarche and start threading the heddles.

Next, threading.

Related posts:

New Loom

Why A Countermarche?

Warping the Glimakra:

.....Adjusting the Loom With Texsolv

.....Threading

.....Tying Up the Treadles

.....The 3 Duhs

.....Adjusting the Shed

....

© 29 June 2007 at http://leighsfiberjournal.blogspot.com

Related posts:

New Loom

Why A Countermarche?

Warping the Glimakra:

.....Adjusting the Loom With Texsolv

.....Threading

.....Tying Up the Treadles

.....The 3 Duhs

.....Adjusting the Shed

....

_raw_A.jpg)

_washed.jpg)